I hope to discuss, in a series of posts, books that have had a significant influence on how I think about and practice architecture. Paraphrasing Thomas Edison, I see architectural design as one part inspiration and ninety-nine parts decision making. The three books I plan to discuss

- Complicity and Conviction: Steps toward an Architecture of Convention by William Hubbard, 1980

- Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution by Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins, and L. Hunter Lovins, 1999

- Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture by Christian Norberg-Schulz, 1979.

address the ninety-nine percent part of the equation. On what basis do we make all of the decisions that ultimately determine what a building looks like, how it is used, and how well it functions? William Hubbard, one of my undergraduate studio professors, described what he called concatenation in design. It occurs when the decision made to solve one problem solves many others and especially when that decision starts a cascade of decisions that simplify what was originally a complex set of problems in design.

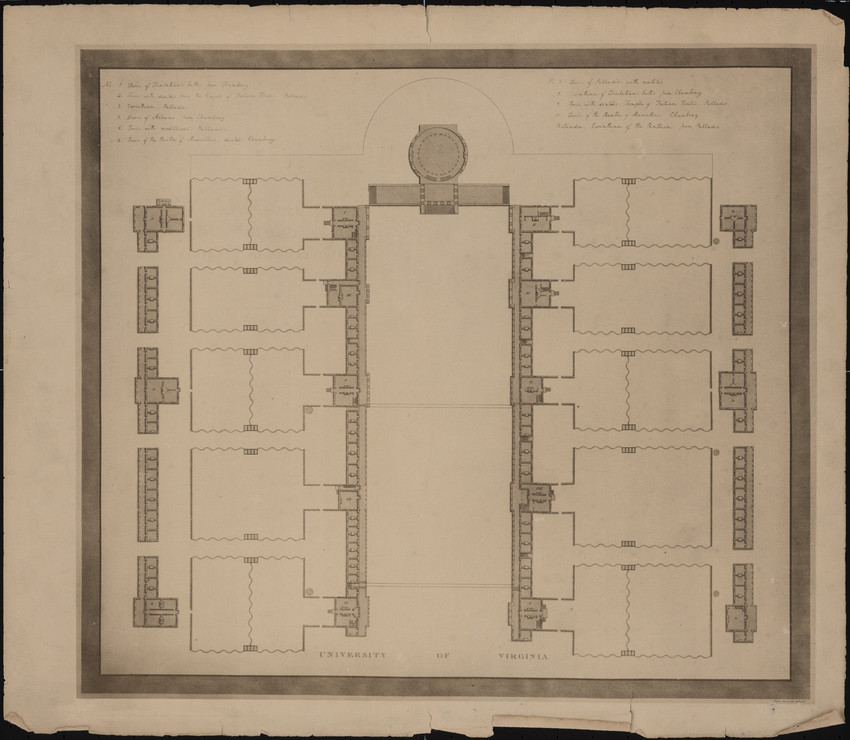

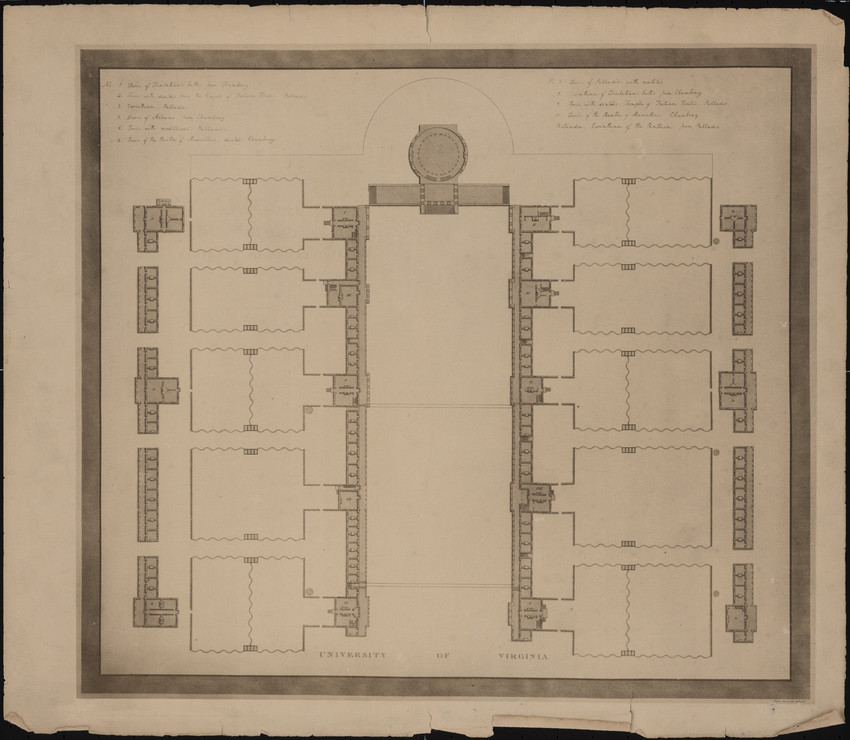

Plan for University of Virginia “lawn” designed by Thomas Jefferson

I did not pick up the first book I want to discuss, Complicity and Conviction, until I was in graduate school. In fact I didn’t know it existed until I saw it at the architecture school library used book sale and saw Bill’s name. My understanding of the book is no doubt influenced by what Bill taught me in Studio. The book is in part a response to Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, 1966. Venturi was criticizing modern architecture and advocating for post modernism, Hubbard was criticizing post-modern architecture and advocating architecture that gives “. . . testimony to human values. . .” Conventional architecture “. . . persuades us to want it to be the way it is.” The book explores several potential models for an architecture of convention:

- The Scenographic Style

- Games

- Typography

- and the Law

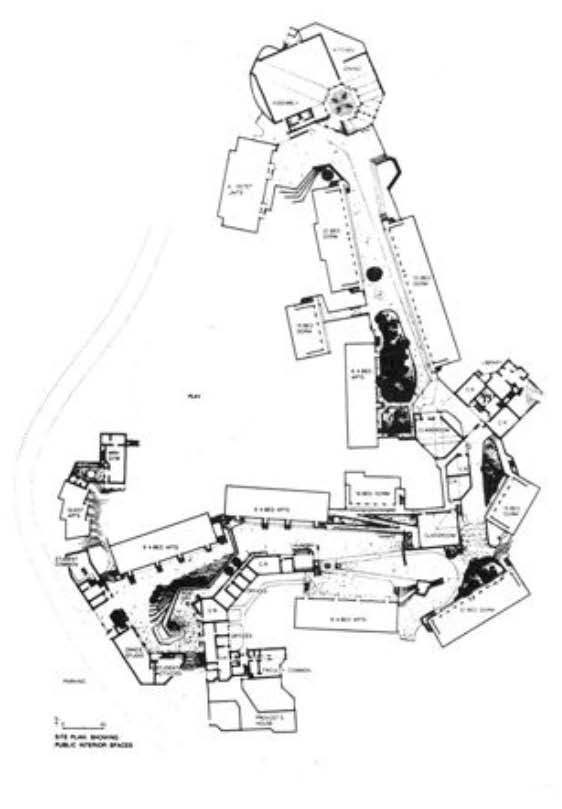

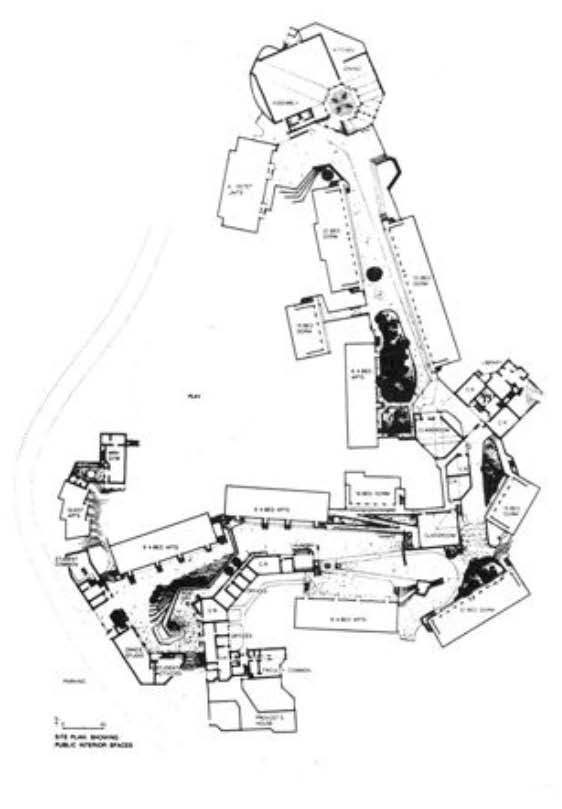

The Scenographic Style encompasses much of American architecture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: the work of H.H. Richardson; the Shingle Style of McKim, Mead & White and John Russell Pope; and the Collegiate Gothic Style of Goodhue and others. He helps us to understand a little more about the design and drawing (sketching) technique that was used at the time. While these buildings make good pictures, he finds that they lack meaningful depth, ultimately leaving us unsatisfied. Games are a set of rules that all of the participants agree to abide by. They are a scrim that allows us to be judged not as a whole person but only by the way we play the game. We accept the rules not because they have to be the way they are, but because they provide a concrete framework in which we can enjoy play. We are complicit, agreeing not to question why the rules are what they are. Typography like architecture can provide a Chinese box of levels of understanding. You do not need to be a typographer to look at a page of text and have a feeling about whether you like the way it looks or how readable it is, but practitioners make very conscious decisions about the shape of the page, the size of the margins, the space between the lines of text, etc. Those decisions are usually made consciously, intending to have an effect on how we feel about the look of the page. The reader has the ability to find reasons for wanting it to be the way it is at many different levels. More understanding brings more reasons to want it the way it is. This depth is one of the aspects that an architecture of convention should have. The Law is perhaps the most interesting model that is discussed. His discussion of the law is limited to the way in which judges construct rulings about which we can feel conviction. The best judgments interpret previous decisions in ways that are consistent with what is currently deemed to be right and fair (this changes over time) and allow enough room for further interpretation in future cases. The judge “forged a new link in the chain” of the law, when he does this. Finally the author analyzes two projects that he believes achieve an architecture of convention in different ways. The first example is the University of Virginia “lawn” designed by Thomas Jefferson in the early nineteenth century and the second is Kresge College at the Santa Cruz campus of the University of California designed by Moore Lyndon Trumbull Whittaker in the early 1970s. The author discusses how each of these projects achieves his six attributes of an architecture of convention:

- Slippage – is the link between the form and its possible uses somewhat ambiguous?

- Contingency – does it have features that make sense only because they feel right?

- Are there multiple possible interpretations of the intention?

- Does it call other buildings to mind?

- Are the analogies relevant?

- Does it make us want it to be as it is and not otherwise?

Plan of Kresge College at the Santa Cruz campus of the University of California designed by Moore Lyndon Trumbull Whittaker

When I first read this book it resonated with some of the discussions we had in the Studio (i.e. The modern world has given us many more options for the materials we use and the way in which we put them together, and air conditioning allows us to ignore many of the implications of how the form, orientation, and construction affect the comfort of the occupants.) The modern world has given the architect more “freedom”. We are allowed to ignore many of the “rules” that used to govern the way we designed. The architectural “rule” books by Vitruvius, Alberti, and Palladio no longer apply. This has left us searching for buildings that improve upon the architecture of the past.

University of Virginia “lawn” designed by Thomas Jefferson

Bill leaves us with a charge: “But to realize that this situation has been brought about by our own actions is to realize that it is within our power to rectify it. It is possible, even now, to produce architecture that gives testimony of human values. . . . We must find ways – in all areas of life – to engender in ourselves conviction about human values. We must find ways to convince ourselves anew of human possibility.”

I could go on forever about all of the amazing architecture and unique cultural experiences that I had in Florence, and I hope to return one day to this beautiful city.

I could go on forever about all of the amazing architecture and unique cultural experiences that I had in Florence, and I hope to return one day to this beautiful city.  As parting words, if you have been to Florence and missed this gem, or if I have inspired you to someday visit, you must go to Gelateria dei Neri for what I am convinced is the most wonderful gelato in the world! I strongly recommend the dark chocolate and pistachio!

As parting words, if you have been to Florence and missed this gem, or if I have inspired you to someday visit, you must go to Gelateria dei Neri for what I am convinced is the most wonderful gelato in the world! I strongly recommend the dark chocolate and pistachio!