Bialosky + Partners Architects is excited to share that Senior Associate and Senior Interior Designer Tracy Sciano Vajskop, IIDA, NCDIQ, LEED ID+C is taking part in the IIDA Ohio Kentucky Chapter's Women's Roundtable: The Future of Women in the Design Industry. The event is tomorrow, hosted by IIDA's Cleveland Akron Chapter on Tuesday June 24th from 5:30pm to 8:00pm at the Home Builders Association of Greater Cleveland, located at 6140 West Creek Road in Independence, Ohio 44131. You can RSVP for the event here: http://www.iidaohky.org/events/cleveland-akron/womens-roundtable-future-women-design-industry-registration-now-open See below for more details! (click image for full size, then zoom)

A lot of construction happened since the last blog post and we have moved into our (mostly) finished house. It is proving to be a very comfortable home and we can hardly wait for winter to see how it performs in the cold. Okay, maybe we can wait a bit for that.

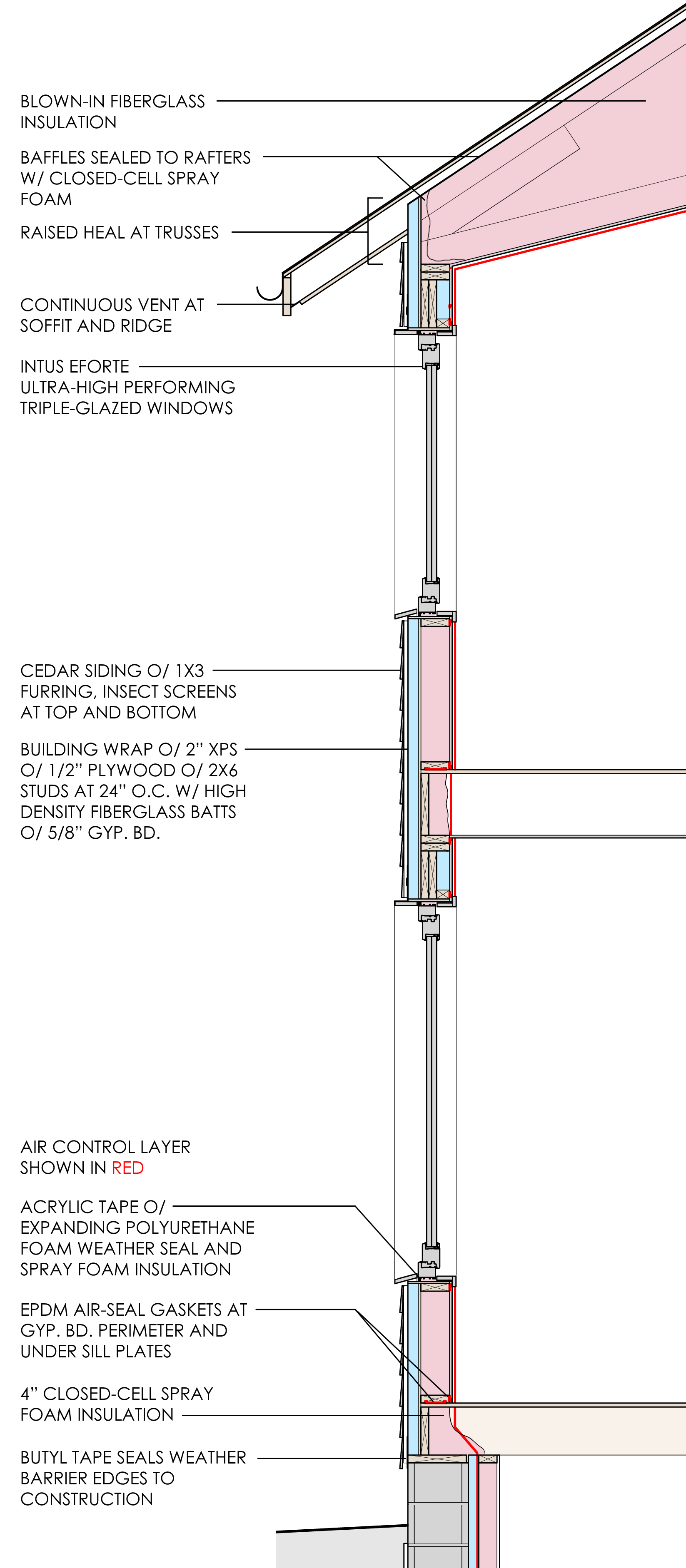

Earlier we explored the foundation system and in this post we’ll discuss the wall and roof systems. Let’s quickly review the four basic control layers to be considered in every building enclosure:

1. Water: Keeps bulk-water out of the structure.

2. Air: Keeps conditioned air inside and unconditioned air outside. Air also holds moisture, so air moving through the structure is a bad thing. As the saying goes, build tight and ventilate right.

3. Vapor: Controls the amount of vapor permeance through the structure. It’s inevitable that some amount of moisture will get into your walls, so you need to allow them to dry-out.

4. Thermal: AKA insulation… Slows the transfer of heat through the structure.

The wall we constructed is a ventilated rainscreen system. A rainscreen is an exterior wall construction where the siding stands off from the weather barrier creating a capillary break allowing for drainage and evaporation. Some of the benefits of this system include prolonged life of the siding and finish (due to temperature and moisture equalization of the material), minimizing the chance of water intrusion into the wall structure, and keeping the weather barrier dry, thereby prolonging its life. To minimize the penetrations through the weather barrier the wall construction was sequenced in this manner: layout studs on floor deck, fasten plywood sheathing to face of wall, place rigid foam board over plywood (only tack in place), roll out building wrap over rigid foam board (do not fasten), place 1x3 furring strips over building wrap (located over each stud), fasten furring strips tight using 4” screws. The furring strips are what hold the building wrap and the insulation board in place. Below is a list of how the 4 control layers were handled:

Water: The metal roofing and underlayment keeps bulk water out of the roof system. The cedar siding is a rainscreen, keeping the bulk water out of the structure. Behind the siding the 3/4" air gap and building wrap act as the drainage plane for any water that makes its way through.

Air: Although great care was taken to control air intrusion at the exterior of the structure by using flashing tapes and minimizing penetrations, the primary air control layer is the gypsum board on the walls and the underside of the roof truss (see red line on diagram). The gypsum board was sealed to the wood structure to prevent air movement from the conditioned spaces into the wall and attic cavities. We used an EPDM gasket that was easy to install and provides an excellent life-long seal. We also used a similar gasket at the wall sill plates to seal the inconsistencies in the wood construction between wall and floor. All rim joists at floor to wall junctures were sealed with spray foam as this is a notorious air-leaking point.

Wall Section Diagram

EPDM Gasket

Vapor: The vapor retarder employed is latex paint over 5/8” gypsum at exterior walls and the 2nd floor ceiling. It’s inevitable that some moisture will make its way into the wall system, so allowing the structure to dry back to the inside is important. Latex paint creates a vapor retarder, not a vapor barrier which would not allow the structure to dry. The attic is continuously ventilated at the eaves as well as the ridge which keeps moisture from building up within the roof structure.

Thermal: The structure of the wall is 2x6 wood studs at 24” o.c. and the cavities are filled with high density fiberglass batts (R-21). To enhance the thermal performance the exterior walls have 2” of XPS (R-10) continuous rigid insulation board. This continuity of insulation eliminates the effects of thermal bridging at the studs, resulting in a very high performing wall system. The attic is filled with blown-in fiberglass at an R-value of 100. The trusses were designed with a raised heal to allow for more insulation at the typical eave pinch-point. Care was taken to seal the baffles to the structure so air from the eave vents would not move through the insulation, stripping it of its thermal performance. The continuous eave and ridge vents keep the attic from becoming super-heated in the summer and keep it cool in the winter which prevents icicles from forming.

Combined with the foundation systems previously discussed and the Intus Eforte ultra-high performing triple-glazed windows, the building shell of the Modern Farmhouse should prove to drastically minimize the amount of energy needed for heating and cooling, all while keeping our family very comfortable.

The sheer variety of building systems that can be used to enclose a structure is astounding. We’ve all come across architects or builders who believe they know the absolute best way to construct a particular building type in a particular environment, but I don’t believe such absolutes truly exist. The appropriate design solution should be arrived at using a balance of project goals, location, efficiency, economy, skill of trades persons, budget, aesthetics, etc. Over the next few months we'll examine the building enclosure of a low-budget, low-energy-use house that my wife and I designed and are currently building for our family.

Panorama of site during excavation.

The very first CMUs are laid on the site for the Modern Farmhouse.

The design intent of this project was to create a simple, right-sized modern farmhouse. One that is beautifully integrated into its site, filled with natural daylight, healthy, comfortable, and uses half the energy of a comparable code-built house….all while sticking to a tight budget. To achieve these goals we had to find a cost effective high performing enclosure system, supplemented by paying careful attention to site orientation and maintaining a compact 2-story form. Decisions were not just based on researching system performance (thank you, www.buildingscience.com ), but also became about choosing systems that our subcontractors would be familiar with. Because we are general contracting the project ourselves and cannot be on site with the subcontractors at all times, a lot of thought was put into choosing the right foundation, wall and roof systems that subs could work with, had construction tolerance, and would still perform. Let’s start with a brief overview of the four basic control layers to be considered in every building enclosure:

1. Water: Keep bulk-water out of the structure.

2. Air: Keep conditioned air inside and unconditioned air outside. Air also holds moisture, so air moving through the structure is a bad thing. As the saying goes, build tight and ventilate right.

3. Vapor: Control the amount of vapor permeance through the structure. It’s inevitable that some amount of moisture will get into your walls, so you need to allow them to dry-out.

4. Thermal: AKA insulation… Slow the transfer of heat through the structure.

Slab-On-Grade Detail

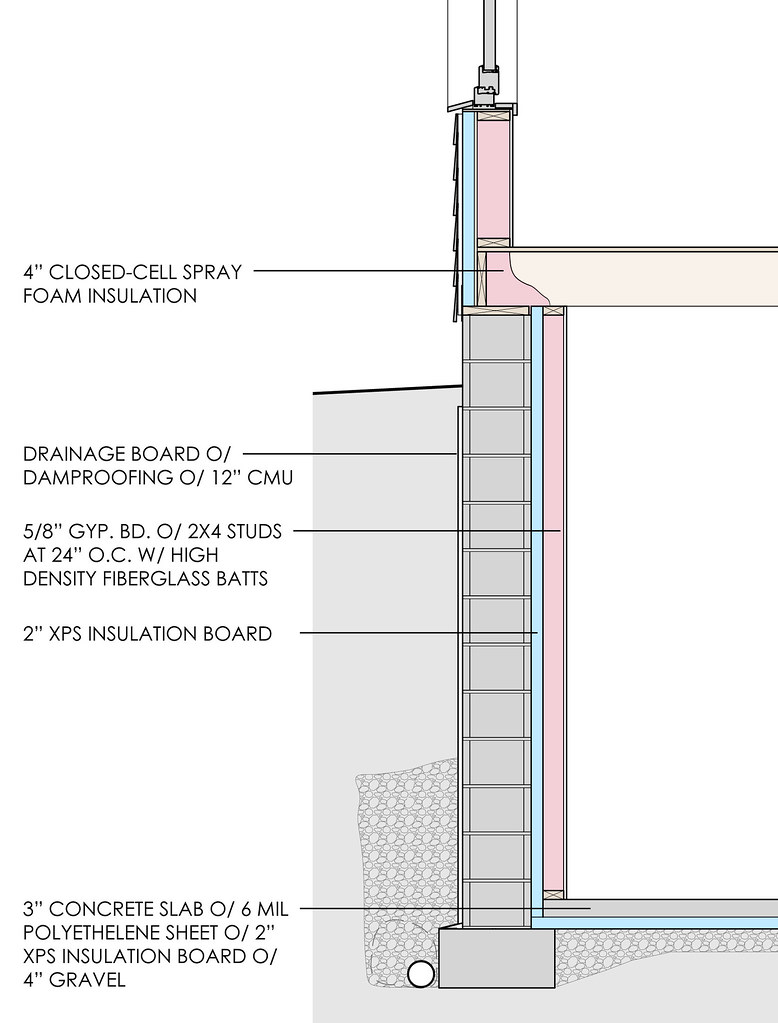

A building needs to be constructed from the foundation up, so that’s where we’ll start. We chose a fairly typical basement structure for Northeast Ohio: 12” CMU on concrete spread footings. What’s different is the type, location and amount of insulation used. To reduce thermal bridging from the earth through the concrete slab and CMU wall, a continuous layer of rigid insulation board was used and the insulation value of the whole system was then increased by adding a 2x4 wall with high density fiberglass insulation. The wall performs on par thermally with insulated concrete forms (a high-performing wall system Bialosky +Partners has used in the past), but is less costly to construct.

Foundation Section of Taylor Residence

Below is a list of how the 4 control layers were handled:

1. Water: The CMU walls were damp proofed and a drainage board placed over top. Together with gravel backfill and foundation drainage that daylights on site the basement should be dry for a lifetime (did I really just say that?).

2. Air: The air control layer is at the interior side of the CMU. Extruded polystyrene (XPS) insulation board was attached with mastic and all joints were sealed to create this layer. High Density closed cell spray foam was installed to seal the first floor system to the XPS. The floor to wall juncture is a notorious air-leaker, so spray foam is a perfect product to seal this area up tight.

3. Vapor: Polyethylene plastic was placed between XPS and concrete slab, and sealed to the CMU wall. This keeps vapor occurring in the ground from driving through the floor slab into the house. Vapor permeable latex paint over 5/8” gypsum board was used as the vapor retarder at the walls. It’s inevitable that some moisture will make its way into the wall system, so allowing the wall to dry back to the inside is important. That’s why we used a vapor retarder, not a vapor barrier which would not allow the wall to dry.

4. Thermal: The XPS board used as an air barrier pulls double duty. 2” XPS (R-10) was used on the walls, and 2” XPS was placed under the entire concrete slab. This continuity of insulation also reduces thermal bridging at the foundation wall and slab. A wall of 2x4 wood studs at 24” o.c. with high density fiberglass batts (R-15) is used to supplement the XPS insulation. 5/8” gypsum board not only finishes the wall system, but is required to meet flame and smoke spread requirements per the building code (XPS foam is not allowed to remain uncovered within an occupiable area). Overall this foundation system is well insulated, didn’t require any special training for the subs, was easy to build, and was inexpensive. I think it was the appropriate choice for this particular project. Next time we’ll examine the house’s wall, floor and roof systems.

For the close of Women's History Month, I've profiled four female architects that may not have made it into our Architecture History courses. These women have each lived over 90 years and together span several decades of design. 1. Anne Tyng (1920 - 2011): Louis Kahn’s Muse Born in China in 1920, Anne Tyng was born to Episcopalian missionaries with an old New England bloodline. Anne was one of the first women to be admitted into the Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1942, where she studied under Walter Gropius, a master and pioneer of modern architecture.

Anne moved to Philadelphia, impressed Louis Kahn, and joined his office, Stonorov & Kahn in 1945. She remained beside him when the firm split in 1947, and would later have a daughter with him after nine years of companionship / partnership. With a passion for geometry and organic forms, she heavily influenced Kahn’s work. She was often regarded as Kahn’s muse, although Bucky Fuller called her "Kahn's geometrical strategist." 2. Marion Mahony Griffin (1871-1961): Frank Lloyd Wright’s First Employee As a small girl, Marion Mahony Griffin, Chicago-born and raised (1871), witnessed the erased landscape of the Great Chicago Fire, and became fascinated with the suburban homes that would infill the void. In 1895, Frank Lloyd Wright hired Marion, a fresh MIT graduate (1894) as his very first employee; she was one of the first women in the world to have a license in architecture. She influenced the development of the Prairie style, which Frank Lloyd Wright is most known for. Marion’s elegant watercolors of buildings and landscapes became synonymous with Wright’s work, though never given credit.

Marion Mahony Griffin, 1936, via savewright.org

When Wright eloped to Europe in 1909, he offered Marion all the studio’s commissions. She declined, and was then hired by Wright’s successor under the condition she would have control of design. Proving it is a small world, Marion married an ex-employee of Wright’s, Walter Burley Griffin, in 1911 to start a partnership that would last 28 years. 3. Eleanor Raymond (1887-1989): Solar House Innovator One client called Eleanor Raymond “an architect who combines a respect for tradition with a disrespect for its limitations.” She was born in Cambridge, MA, and would later earn many commissions for homes in New England through her social circles. Eleanor first began work with Henry Atherton Frost, an advocate for clear, simple design. Eleanor brought this sentiment to her own practice in 1928, where she became a mover and shaker of residential design. Eleanor designed one of the very first houses in the International Style (which was recently listed for sale in 2013), and continued to revolutionize residential design as an early adopter of "Adaptive-Re-Use". Her passion for historic preservation was gracefully balanced with the profound interest in new and innovative materials; she designed a Plywood House in 1940, and the Dover Sun House in 1948, the first occupied solar-powered house in the U.S.

4. Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999): Le Corbusier's Furniture Design Muscle After looking at her application, Le Corbusier told the 24 year old Parisienne furniture designer Charlotte Perriand in 1927, "We don't embroider cushions here". He changed his tune a few months later, once her work was on display at the Salon d'Automne, and then offered her a job. One year later, Charlotte ushered in the 'machine age' aesthetic to interiors, and designed the three most iconic chairs attributed to Le Corbusier. We still love (and replicate) them today: the B301 (Basculant Sling Chair), the B306 (The Chaise Lounge), and the LC2 Grand Comfort.

In the 1930s, Charlotte became involved in many leftist organizations, such as the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires (AEAR) for revolutionary artists and writers, and later helped to found The Union des Artistes Modernes. All this instilled in her the value of producing affordable accessible design for the people. But the legacy-builders are not all in the past. The truth is, the momentum is still there for female rising-stars. They are starting their own firms, like Carrie Strickland. They are teaching and experimenting at schools of design, like Florencia Pita and Jacklin Hah Bloom. This year's AIA National Convention in Chicago includes Architect and MacArthur “genius grant” winner Jeanne Gang, FAIA, founder of Studio Gang Architects as a featured keynote. AIA recently posthumously awarded the 2014 Gold Medal to Julia Morgan, FAIA, the first time their highest award has been bestowed upon a women. Women are even approaching the golden "50-50 mix" of female-to-male project teams, like Marianne Kwok. But the key word is "approaching". That 50-50 mix generally true in our architecture schools (think back to your college days), but yet only 18% of registered architects are female. This is exactly what initiatives such as AIA San Francisco's The Missing 32% Project, is investigating, the (slowly depleting, but still present) gender gap in the profession. But the open dialog around women in architecture is more vibrant now than ever before. From my own experience, it is exciting to see females in our own firm becoming registered, leading design teams, and being promoted! Some day, it will not be labeled as "conventionally male profession", but just plainly "the profession".

Last Friday I put together a small informal internal lunch and learn for the BPA staff in which we looked at and discussed digital fabrication equipment and construction techniques. Based off of the course that I taught at Kent State University last semester, the discussion of various techniques and uses in architectural applications became very exciting. We also began to discuss and share how the process of scripting and parametric design could impact our design. I shared various precedent from firms such as SHoP Architects, design work by Alex Hogrefe, and even included some of my own work on a new bookshelf that is in process. Feel free to walk through the Prezi Presentation below!

[prezi id="<http://prezi.com/jhgvwfbugqxo/macraild-dig-fab-and-parametric-modelling-lunch-and-learn/#>" width=500 height=400 lock_to_path=0]